Three centuries of music, from 1740 to the present

1740-1790

The origins of the theatre date to the beginning of the 18th Century, when Vittorio Amedeo II commissioned architect Filippo Juvarra to design and construct a grand new theatre as part of the more general urban reorganization of Piazza Castello.

The origins of the theatre date to the beginning of the 18th Century, when Vittorio Amedeo II commissioned architect Filippo Juvarra to design and construct a grand new theatre as part of the more general urban reorganization of Piazza Castello.

The intention, however, was completed only a few years later by Carlo Emanuele III (crowned king in 1730) who, after the death of Juvarra, chose to entrust the project to architect Benedetto Alfieri, with the demand to design a very prestigious theatre. The «Teatro Regio» of Torino, built in the record time of two years, was inaugurated on 26 December 1740 with Arsace by Francesco Feo. It immediately became an international reference point because of its capacity – about 2,500 seats among the stalls and the five tiers of boxes –, the magnificent decorations in the auditorium with the vault painted by Sebastiano Galeotti, the impressive scenes and the technical equipment, as well as the quality of the performances.

Each season began on 26 December, concluded with the end of Carnival and included two new opere serie written specially for the Teatro. During the 18th Century such celebrated Italian composers as Galuppi, Jommelli, Cimarosa and Paisiello wrote for the Regio, as did foreign authors like Gluck, Johann Christian Bach and Hasse. Moreover, the most famous castratos and prima donnas of the epoch sang there, contributing in a decisive way to the success of the performances. Arousing no less interest were the dancers, who appeared in the two entr’acte dances and in the final choreographic action that was part of each opera.

- See more about period 1740-1790

-

1.1 Alfieri’s theatre

The Teatro Regio, on the left side in the engraving by Giambattista Borra (1749), is camouflaged in the middle of the adjoining architecture of the buildings in Piazza Castello, from Palazzo Reale to via Po.

The Teatro Regio, on the left side in the engraving by Giambattista Borra (1749), is camouflaged in the middle of the adjoining architecture of the buildings in Piazza Castello, from Palazzo Reale to via Po.Set in the old command zone that included the nerve centres of life in the Savoy state, it was the instrument of entertainment and for celebrating the stability of power. The connection with the court was also physically reasserted by the possibility for the royal family and other dignitaries to get to the theatre from Palazzo Reale without having to go out into the street, or rather by way of the Beaumont Gallery (today the Royal Armoury) and the palazzo of the Secretaries (today the Prefecture).

1.2 A destination of the Grand Tour

The large elliptical auditorium is furnished with 152 boxes divided in five tiers and embellished with crimson and gold decorations. The foreign travellers who made the Grand Tour to discover the beauties of the peninsula describe the theatre with great admiration in their memoirs.

Charles Burney, one of the foremost musical historians, mentioned it in The Present State of Music in France and Italy as «the great opera theatre that is considered one of the most beautiful in Europe».

In 1761, the Royal Printing House published the engravings by Giovanni Antonio Belmondo, based on original designs by Alfieri, to reveal the splendours of the Savoy dynasty throughout Europe. Reproduced in various treatises on architecture, the plates received a definitive consecration with their publication, in 1772, in the Encyclopédie di Diderot e D’Alembert

1.3 The opera hall

The preparatory designs and the engravings let us see some of the innovative characteristics of the Teatro, such as the shell under the orchestra to improve the acoustic output, the oblique orientation of the boxes towards the stage, and the arrangement of the five tiers surmounted by the upper gallery, or pigeon hole.

The preparatory designs and the engravings let us see some of the innovative characteristics of the Teatro, such as the shell under the orchestra to improve the acoustic output, the oblique orientation of the boxes towards the stage, and the arrangement of the five tiers surmounted by the upper gallery, or pigeon hole.Unlike French theatres, the Regio did not have fixed seats, but ones that could be moved by the audience: the Teatro was not just for shows, but also a meeting place where one could get together for conversation, eating or gambling. Inside the Regio a few shops were opened (like the «refreshments shop» and the one of the «courtesies»), contracted by the Knights’ Society.

1.4 The scenery

After calling to Turin, with annual appointments, such great stage designers as Crosato and Giuseppe Galli Bibiena, who designed the scenes for the inaugural opera, Arsace, the Knights’ Society assured themselves of the regular collaboration of “resident” stage designers, the «Signori Fratelli Galliari»: Bernardino, Fabrizio and Giovanni Antonio, later joined by Fabrizio’s sons, Giovannino and Giuseppino, active until the end of the century.

After calling to Turin, with annual appointments, such great stage designers as Crosato and Giuseppe Galli Bibiena, who designed the scenes for the inaugural opera, Arsace, the Knights’ Society assured themselves of the regular collaboration of “resident” stage designers, the «Signori Fratelli Galliari»: Bernardino, Fabrizio and Giovanni Antonio, later joined by Fabrizio’s sons, Giovannino and Giuseppino, active until the end of the century.Sketches and engravings that have come down to us illustrate the evolution from rather undefined subjects, tied to the Metastasian librettos, to a greater variety of settings which, starting from the 1760s and 1770s, included the world of the Middle Ages, Egyptian civilization, chinoiseries and pre-Colombian civilizations.

1.5 The original curtain

The curtain of the Teatro, made for the inauguration by Sebastiano Galeotti and representing the Triumph of Bacchus, was quickly restored because damaged by the rigid framework and smoke from the lamps. In 1756 it was substituted by one on the same subject made by stage designer Bernardino Galliari, who had already made the curtain for Teatro Carignano and had been active since 1747 as stage designer of the Regio, together with his brother Fabrizio.

The curtain of the Teatro, made for the inauguration by Sebastiano Galeotti and representing the Triumph of Bacchus, was quickly restored because damaged by the rigid framework and smoke from the lamps. In 1756 it was substituted by one on the same subject made by stage designer Bernardino Galliari, who had already made the curtain for Teatro Carignano and had been active since 1747 as stage designer of the Regio, together with his brother Fabrizio.The chiaroscuro style and the choice of colours ensured the success of the author, who became one of the favourite decorators of the Torinese aristocracy.

1.6 Paisiello at the Regio

In January 1771, having reached Turin from Milan, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and his father Leopold had the opportunity to see «a magnificent opera» at the Regio: Annibale in Torino by Giovanni Paisiello. In those years Paisiello was one of the composers most in vogue in Naples, where he was trained, and his fame was spreading throughout Europe (in just a few years he would be invited to St Petersburg by Catherine II).

In January 1771, having reached Turin from Milan, Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart and his father Leopold had the opportunity to see «a magnificent opera» at the Regio: Annibale in Torino by Giovanni Paisiello. In those years Paisiello was one of the composers most in vogue in Naples, where he was trained, and his fame was spreading throughout Europe (in just a few years he would be invited to St Petersburg by Catherine II).After the successes, especially in the buffo genre, the Regio gave Paisiello one of the first important commissions for an opera seria. The libretto, by the Piedmontese lawyer Jacopo Durandi, describes the clash and reconciliation between Hannibal and King Artace of the Taurini.

1.7 Prima donnas and castratos

In the 18th Century, singers and ballerinas were hired for the entire season rather than for the single opera. Crucial to the success of the performance, they were also the most expensive item of expenditure for the organizers. Among the “prima donnas” who performed at the Regio, at least as famous for their tantrums as for their vocal qualities, one recalls Lucrezia Agujari, Caterina Gabrielli and Brigida Giorgi Banti.

In the 18th Century, singers and ballerinas were hired for the entire season rather than for the single opera. Crucial to the success of the performance, they were also the most expensive item of expenditure for the organizers. Among the “prima donnas” who performed at the Regio, at least as famous for their tantrums as for their vocal qualities, one recalls Lucrezia Agujari, Caterina Gabrielli and Brigida Giorgi Banti.The Regio, moreover, witnessed the last phase of the golden age of the castratos: singing there were Giovanni Carestini in art “il Cusanino”, Gioachino Conti known as “il Gizziello”, Gaetano Majorana “il Caffarelli”, and Gaetano Guadagni. Luigi Marchesi, depicted here in Achille in Sciro (1785) written for him by Gaetano Pugnani, was engaged by the Regio for three seasons and named “first virtuoso of chapel and chamber” by the King of Sardinia.

While the names in the world of song were all Italian, for dance there was a strong French influence: the Torino court saw the arrival of many choreographers, dance maestros and ballerinas from the other side of the Alps, including François Sauveterre, Jean Dauberval and Sébastien Gallet, but also such celebrated Italian choreographers as Gasparo Angiolini. Great musicians performed at the Teatro, like Giovanni Paisiello, who met with enormous success above all in the buffo genre, and Gaetano Pugnani, named first violin of the Teatro and Royal Chapel in 1770.

1790-1814

After being closed for five years (1792-1797) the Regio changed name several times, reflecting the changes in historical events: in 1798 it became Teatro Nazionale, in 1801 Grand Théâtre des Arts and in 1804 Théâtre Impérial.

After being closed for five years (1792-1797) the Regio changed name several times, reflecting the changes in historical events: in 1798 it became Teatro Nazionale, in 1801 Grand Théâtre des Arts and in 1804 Théâtre Impérial.

In the moralizing climate of the Republican years gambling was abolished and hiring castratos was prohibited (they would later return in the Imperial Age). Italian operas continued to be in the repertoire, with the librettos more or less superficially adapted to suit Jacobinic taste. Napoleon attended performances there on three occasions and the very finest artists like the soprano Isabella Colbran, the tenor Nicola Tacchinardi and the choreographer Salvatore Viganò also came to Torino.

- See more about period 1790-1814

-

2.1 The private impresarios

In the French period the management of the theatre passed from the Knights’ Society to the municipality, with a succession of private impresarios who often pulled out following financial failures.

In the French period the management of the theatre passed from the Knights’ Society to the municipality, with a succession of private impresarios who often pulled out following financial failures.Between 1801 and 1803 management passed to Giacomo Pregliasco, today remembered above all as the originator of splendid costumes not only for the Regio of Torino, but also for Scala of Milan and the San Carlo of Naples.

In his activity as impresario, Pregliasco tried to extend the opening period of the Teatro and also welcomed opere giocose there, but it was a brief experiment and the former distinction between the genres was soon re-established.

2.2 The Théâtre Impérial

In 1804 the Teatro became Théâtre Impérial: the use of the royal box, abolished in the Republican years, was brought back, and Napoleon expected that it would be reserved exclusively for his use and remain closed except in his absence. In December 1807, the cantata L’incoronazione and the allegory Le retour de la Grande Armée were presented for the emperor’s arrival in Turin.

In 1804 the Teatro became Théâtre Impérial: the use of the royal box, abolished in the Republican years, was brought back, and Napoleon expected that it would be reserved exclusively for his use and remain closed except in his absence. In December 1807, the cantata L’incoronazione and the allegory Le retour de la Grande Armée were presented for the emperor’s arrival in Turin.In addition to the shows of the season, the Teatro was the venue for celebrations during visits by the emperor and reigning princes, Camillo and Paolina Borghese. The emperor’s sister stayed in Torino only a few months in 1808, but from 1809-1814 her saint’s day was celebrated at the Théâtre Impérial with the staging of laudatory cantatas, a sort of tableaux vivants of pastoral-mythological subjects.

2.3 Isabella Colbran

In those years, the Teatro Regio had as guest the Spanish opera star Isabella Colbran, one of the finest interpreters of the early nineteenth century. Famous for her voice and her beauty, she was also celebrated for her acting ability in operas such as Nitteti by Stefano Pavesi, I riti d’Efeso e Lauso e Lidia by Giuseppe Farinelli, Castore e Polluce by Vincenzo Federici and Gerusalemme distrutta, a sacred work by František Dušek.

In those years, the Teatro Regio had as guest the Spanish opera star Isabella Colbran, one of the finest interpreters of the early nineteenth century. Famous for her voice and her beauty, she was also celebrated for her acting ability in operas such as Nitteti by Stefano Pavesi, I riti d’Efeso e Lauso e Lidia by Giuseppe Farinelli, Castore e Polluce by Vincenzo Federici and Gerusalemme distrutta, a sacred work by František Dušek.2.4 The staging by Maurizio Sevesi

Fabrizio Sevesi, nephew and student of the Galliaris, created the stage sets of the Regio from 1800 to 1837, along with Luigi Vacca, by following the variations in taste from Neo-classicism to Romanticism and by adapting to political changes.

Fabrizio Sevesi, nephew and student of the Galliaris, created the stage sets of the Regio from 1800 to 1837, along with Luigi Vacca, by following the variations in taste from Neo-classicism to Romanticism and by adapting to political changes.It was not unusual for scenery to be modified and reused on various occasions: for Maria Cristina’s birthday, for example, the scenery for the celebrations of Paolina Borghese were used again, substituting the epigraphs exalting Napoleon with the coats of arms of the Bourbons and the Savoys.

1815-1870

The Savoys regained possession of the theatre with the Restoration. At the time of Carlo Felice, a great lover of music, virtuosos like Giuditta Pasta and Domenico Donzelli performed on stage at the Regio, but in the nineteenth century Torino lost its importance compared to Milan, Naples and Venice.

The Savoys regained possession of the theatre with the Restoration. At the time of Carlo Felice, a great lover of music, virtuosos like Giuditta Pasta and Domenico Donzelli performed on stage at the Regio, but in the nineteenth century Torino lost its importance compared to Milan, Naples and Venice.

Under Carlo Alberto the auditorium received a Neo-classical imprint (emphasized by the renovation works entrusted to Ernesto Melano and Pelagio Palagi). In the middle of the century a few changes were introduced in the programming. There was a shift to the season of Carnival-Lent, divided into five or more mainly repertoire operas (and no longer those written specially for the Teatro). Furthermore, beginning with Rossini’s Barbire di Siviglia (1855), the Regio opened up to opera buffa.

New renovations by Angelo Moja in 1861 did away with the changes made by Pelagi and gave the auditorium a “Neo-baroque” appearance.

- See more about period 1815-1870

-

3.1 Neo-classical architecture

The programme of architectural renewal with which Carlo Alberto intended to give his own imprint to the Savoy capital could not ignore the Teatro of the crown: the restructuring of the auditorium was entrusted to the architect Ernesto Melano and the Bolognese painter Pelagio Palagi, also active at the building sites of Palazzo Reale, the Biblioteca Reale and Castello di Racconigi.

The programme of architectural renewal with which Carlo Alberto intended to give his own imprint to the Savoy capital could not ignore the Teatro of the crown: the restructuring of the auditorium was entrusted to the architect Ernesto Melano and the Bolognese painter Pelagio Palagi, also active at the building sites of Palazzo Reale, the Biblioteca Reale and Castello di Racconigi.As is evident from the picture taken when Grand Duke Alexander of Russia visited (1839), the Teatro had assumed an austere Neo-classical imprint, with the elimination of the Baroque curves and the use of Corinthian columns.

3.2 Giuditta Pasta and Adelina Patti

Giuditta Pasta, one of the most celebrated singers of the early nineteenth century, debuted in Milan in 1815 and soon made a name for herself in other Italian cities, in Paris and in London. Adored by Stendhal, she was the leading lady in the “premières” of Sonnambula, Norma and Beatrice di Tenda by Bellini and Anna Bolena by Donizetti. After her debut at the Teatro Carignano in 1820, she returned to Torino for the 1821-22 season of the Regio, where she met with enormous success in I riti d’Efeso by Giuseppe Farinelli and Rossini’s Edoardo e Cristina.

Giuditta Pasta, one of the most celebrated singers of the early nineteenth century, debuted in Milan in 1815 and soon made a name for herself in other Italian cities, in Paris and in London. Adored by Stendhal, she was the leading lady in the “premières” of Sonnambula, Norma and Beatrice di Tenda by Bellini and Anna Bolena by Donizetti. After her debut at the Teatro Carignano in 1820, she returned to Torino for the 1821-22 season of the Regio, where she met with enormous success in I riti d’Efeso by Giuseppe Farinelli and Rossini’s Edoardo e Cristina.In the second half of the nineteenth century, after the theatre programmes were amplified, the singers were no longer signed on for the entire season but for individual operas instead.

In 1865, the Regio audience had the opportunity to hear Adelina Patti, the diva par excellence in the world of opera, in four out-of-season performances of Bellini’s Sonnambula and Rossini's Barbiere di Siviglia. She would then return to Torino in 1879 for Traviata. Verdi had appreciated her two years earlier describing her this way: «marvellous voice, very pure singing style; stupendous actress with a charm and a natural that nobody else has».

3.3 Polledro and Mercadante

Under Carlo Felice there was a reorganization of the Royal Chapel, which provided most of the instrumentalists for the Teatro orchestra. Giovanni Battista Polledro (1823), Pugnani’s student and a celebrated virtuoso, was named first violin, a position he had already held in Dresden.

Under Carlo Felice there was a reorganization of the Royal Chapel, which provided most of the instrumentalists for the Teatro orchestra. Giovanni Battista Polledro (1823), Pugnani’s student and a celebrated virtuoso, was named first violin, a position he had already held in Dresden.In Torino, Polledro improved the level of the orchestra and introduced the great compositions of instrumental music by the composers of Viennese classicism, acquiring a number of scores by German editors for the Royal Chapel.

In the same years, Saverio Mercadante, who was trained in Naples, started his international career with the success of Elisa e Claudio, presented in Milan in 1821. He was the only major composer of the time to have a privileged rapport with the Regio of Torino, where he presented in absolute “première” Didone abbandonata (1823), Nitocri (1824), Ezio (1827), I Normanni a Parigi (1832), Francesca Donato, ovvero Corinto distrutta (1835), Il reggente (1843) and six other operas that had already been staged in other theatres.

3.4 The romantic ballet

The principal exponents of romantic ballet were guests at the Regio in the 1830s and 1840s: Fanny Cerrito debuted at the Regio in the 1835-36 season and returned there ten years later, after great success in the major European capitals. Natalie Fitz-James and Arthur Saint-Léon danced together in the Italian “première” of Giselle (1842). In January 1845 the Torinese audience applauded the “divine” Maria Taglioni, creator of La Sylphide and symbol of the romantic ballerina, who interpreted L’allieva d’Amore, ballet presented with Bellini’s Norma.

The principal exponents of romantic ballet were guests at the Regio in the 1830s and 1840s: Fanny Cerrito debuted at the Regio in the 1835-36 season and returned there ten years later, after great success in the major European capitals. Natalie Fitz-James and Arthur Saint-Léon danced together in the Italian “première” of Giselle (1842). In January 1845 the Torinese audience applauded the “divine” Maria Taglioni, creator of La Sylphide and symbol of the romantic ballerina, who interpreted L’allieva d’Amore, ballet presented with Bellini’s Norma.Attention for the dance was also evidenced by the restructuring of the dance school commissioned by Carlo Alberto in 1846. Thanks to the new involvement of the crown, the school proved to be one of the most prestigious in Italy, alongside those in Milan and Naples.

1870-1936

In 1870 the City of Turin took over ownership of the Regio. In those years the history of the Teatro interwove with that of the Civic Orchestra and the Popular Concerts conceived by Carlo Pedrotti, who brought important novelties to the repertoire by introducing the music of Wagner and Massenet in the programming. The debut of Arturo Toscanini at the Teatro was also in the name of Wagner. The Maestro collaborated with the Orchestra from 1895 to 1898 and on 26 December 1905, after the renovations supervised by Ferdinando Cocito, inaugurated the new auditorium with Siegfried.

In 1870 the City of Turin took over ownership of the Regio. In those years the history of the Teatro interwove with that of the Civic Orchestra and the Popular Concerts conceived by Carlo Pedrotti, who brought important novelties to the repertoire by introducing the music of Wagner and Massenet in the programming. The debut of Arturo Toscanini at the Teatro was also in the name of Wagner. The Maestro collaborated with the Orchestra from 1895 to 1898 and on 26 December 1905, after the renovations supervised by Ferdinando Cocito, inaugurated the new auditorium with Siegfried.

Other important composers in the history of the Regio are Giacomo Puccini, who christened Manon Lescaut (1893) and La bohéme (1896) in Turin, and Richard Strauss, who in 1906 conducted Salome in the Italian “première”. The last great “première” held by the old Regio was Francesca da Rimini by Riccardo Zandonai, libretto by Gabriele D’Annunzio (1914). After being closed during the wartime period, the Teatro dedicated itself to repertoire operas.

During the night of 8 and 9 February 1936 the Teatro was destroyed by a violent fire and it would take almost forty years to rebuild it.

- See more about period 1870-1936

-

4.1 Pedrotti and the Popular Concerts

Carlo Pedrotti, assuming the position of rehearsal coach and conductor of the Regio orchestra in 1868, gave a considerable boost to the concert activity by founding the Popular Concerts, the first public concert institution in Italy.

Carlo Pedrotti, assuming the position of rehearsal coach and conductor of the Regio orchestra in 1868, gave a considerable boost to the concert activity by founding the Popular Concerts, the first public concert institution in Italy.Even though they took place outside the opera season at the Teatro Vittorio Emanuele, where the “Arturo Toscanini" Auditorium Rai stands today, the Popular Concerts belong to the history of the Regio precisely because they had as protagonist the Teatro Orchestra.

The sixty-four concerts held between 1872 and 1886 offered the Torinese audience a panorama of classical, romantic and contemporary symphonic repertoire, creating a new interest in instrumental music that was still not cultivated very much in Italy at the time.

4.2 Wagnerian Torino

One of the great novelties introduced by Pedrotti was the music of Wagner, who also aroused impassioned debate in the drawing rooms and literary circles in Italy. Pedrotti directed a few pieces of Lohengrin as part of the Popular Concert series in 1872 and five years later, with the support of the impresario Giovanni Depanis, proposed the entire opera at the Regio, translated into Italian and with staging by Richard Fricke, Wagner’s collaborator in Bayreuth.

One of the great novelties introduced by Pedrotti was the music of Wagner, who also aroused impassioned debate in the drawing rooms and literary circles in Italy. Pedrotti directed a few pieces of Lohengrin as part of the Popular Concert series in 1872 and five years later, with the support of the impresario Giovanni Depanis, proposed the entire opera at the Regio, translated into Italian and with staging by Richard Fricke, Wagner’s collaborator in Bayreuth.After the young opera Rienzi (1882), the entire Tetralogy was presented in 1883 in the original language and with staging by the company of Angelo Neumann, which held the exclusive rights for a European tour. Later Turin contended with Bologna for the title of “Wagnerian city” of Italy, presenting, among other things, Lohengrin with Roberto Stagno (1885) and Tannhäuser with Giovanni Battista De Negri (1888), and then the “prima” in Italy, in Italian, of Die Walküre (1891) and Götterdämmerung (1895) directed by Toscanini.

In the years of Depanis’s management (1877-1881), the Regio reacquired a leading position on the Italian scene: without neglecting operas from the Donizetti and Verdi repertoires, the theatre programmes presented Italian “premières” of operas by composers who were still relatively unknown in our country.

4.3 The “grand pas”

In the 1870s and 1880s dance at the Regio saw a final phase of splendour before the crisis that would lead to the closure of the dance school in 1890. It was the time of the “Grand pas”, characterised by great masses of ballet dancers and impressive scenic displays.

In the 1870s and 1880s dance at the Regio saw a final phase of splendour before the crisis that would lead to the closure of the dance school in 1890. It was the time of the “Grand pas”, characterised by great masses of ballet dancers and impressive scenic displays.The settings ranged from the Wagnerian influence of German mythology in Sieba, or La spada di Wodan (1878) to the historical reconstructions of Cristoforo Colombo (1893). In 1882, Excelsior also triumphed in Turin after its success at La Scala. The ballet by choreographer Luigi Manzotti and composer Romualdo Marenco was a monumental allegory of the victory of Civilization and Light over obscurantism.

4.4 Alfredo Catalani

Alfredo Catalani had a superior rapport with Turin: at Regio he obtained significant success with the “première” of Elda (1880), represented later in a revised form with the title Loreley (1890). Dejanice, a year after the “première” at La Scala, was staged as part of the shows for the Esposizione Generale Italiana of 1884, with the direction of Franco Faccio and Gemma Bellincioni in the role of Argelia.

Alfredo Catalani had a superior rapport with Turin: at Regio he obtained significant success with the “première” of Elda (1880), represented later in a revised form with the title Loreley (1890). Dejanice, a year after the “première” at La Scala, was staged as part of the shows for the Esposizione Generale Italiana of 1884, with the direction of Franco Faccio and Gemma Bellincioni in the role of Argelia.La Wally, finally, was performed in Turin in 1894 with at least a one year delay compared with the wishes of the composer, who in the meantime departed prematurely because of the strong influence of the music publisher Casa Ricordi, which conditioned the artistic choices of the theatres and had given precedence to Puccini’s Manon Lescaut.

4.5 Arturo Toscanini

Nine years after the debut in Torino at the Teatro Carignano in 1886 with Edmea by Catalani, Toscanini debuted at the Regio by inaugurating the 1895-96 season with the Italian première of Götterdämmerung (with translated text).

Nine years after the debut in Torino at the Teatro Carignano in 1886 with Edmea by Catalani, Toscanini debuted at the Regio by inaugurating the 1895-96 season with the Italian première of Götterdämmerung (with translated text).From that moment on, Toscanini’s contribution was fundamental to the success of Wagnerian music in Turin and Italy: Tristan und Isolde (1897), Die Walküre (1898) and Siegfried (1905) would follow. The great success with the critics and the audiences also marked the

beginning of a strong and profitable relationship with the Municipal Orchestra, which Toscanini directed until April 1898. Giacomo Grosso, Portrait of Arturo ToscaniniThis collaboration had as significant stages the series of 43 concerts for the Esposizione Generale Italiana in Torino in 1898 and the five concerts on the occasion of the Esposizione Internazionale of 1911.

beginning of a strong and profitable relationship with the Municipal Orchestra, which Toscanini directed until April 1898. Giacomo Grosso, Portrait of Arturo ToscaniniThis collaboration had as significant stages the series of 43 concerts for the Esposizione Generale Italiana in Torino in 1898 and the five concerts on the occasion of the Esposizione Internazionale of 1911.At the Regio, Toscanini objected to the excessive power of the leading artists. He ordered them to respect the scores, and tried to shift the audience’s interest from the performance of the singer-diva to the totality of the opera, in which the singing, instrumental performance and staging are coordinated by the director.

4.6 Giacomo Puccini

La Bohème, which went on stage on 1 February 1896, was Puccini’s third opera to be presented in absolute “première” at the Regio after Le Villi (adaptation of Le Willis, 1884) and Manon Lescaut (1893). On the orchestra podium was Arturo Toscanini, who would also direct Madama Butterfly in 1906.

La Bohème, which went on stage on 1 February 1896, was Puccini’s third opera to be presented in absolute “première” at the Regio after Le Villi (adaptation of Le Willis, 1884) and Manon Lescaut (1893). On the orchestra podium was Arturo Toscanini, who would also direct Madama Butterfly in 1906.Manon was an immediate success with the audience and the critics, whereas La Bohème did not meet with approval initially. While the Milanese press praised the composer, the magazines in Turin and in particular the «Rivista Musicale Italiana», advocate of Wagnerian music, expressed unfavourable opinions. The audience in the auditorium, however, gave lengthy applause to the composer, the conductor and the cast, including the Torinese soprano Cesira Ferrani in the role of Mimì.

4.7 The renovation

From 1901 to 1905 the Teatro Regio was ordered closed by the committee of inspection because of the precarious condition of the building. The question of building a new theatre was discussed at length, but in the end it was decided to renovate it, entrusting the structural work to Ferdinando Cocito and the decorative parts to Giorgio Ceragioli.

From 1901 to 1905 the Teatro Regio was ordered closed by the committee of inspection because of the precarious condition of the building. The question of building a new theatre was discussed at length, but in the end it was decided to renovate it, entrusting the structural work to Ferdinando Cocito and the decorative parts to Giorgio Ceragioli.In the renovated auditorium, the last two tiers of boxes were substituted by three galleries, bringing the overall seating capacity of the auditorium to about 3,000 seats, and the Teatro assumed a more “popular” appearance: no longer a haunt of the aristocracy, but reflecting the social changes that had taken place not only in the city but elsewhere as well.

4.8 The fire

During the cold night between 8 and 9 February 1936, while Mulè’s Liolà was on the bill, a fire broke out in the subterranean area of the stage, where there were wooden beams and scaffolding crossed by myriads of electrical cables.

During the cold night between 8 and 9 February 1936, while Mulè’s Liolà was on the bill, a fire broke out in the subterranean area of the stage, where there were wooden beams and scaffolding crossed by myriads of electrical cables.The blaze destroyed the Teatro, built almost two hundred years earlier. Despite the immediate intervention of the Fire Brigade and the soldiers of the Corps of Engineers, the spread of the fire was «sudden and very violent» and the flames soon reached the auditorium as well. At two in the morning, thousands of Torinese flocked to piazza Castello, powerless in front of “their” Teatro ablaze.

1936-1973

After the fire of 1936, there was the problem of deciding who should be in charge of the project of reconstructing the Teatro. The announcement of competition published in 1937 was won by the architects Aldo Morbelli and Robaldo Morozzo della Rocca. Their project, however, was never fully accomplished.

After the fire of 1936, there was the problem of deciding who should be in charge of the project of reconstructing the Teatro. The announcement of competition published in 1937 was won by the architects Aldo Morbelli and Robaldo Morozzo della Rocca. Their project, however, was never fully accomplished.

In 1965, in fact, the city administration proposed a new solution by entrusting the work to architect Carlo Mollino and engineer Marcello Zavelani Rossi. The work began in early September 1967 and was completed in the very first months of 1973.

- See more about period 1936-1973

-

5.1 The announcement of competition

The announcement of the competition to assign the project of reconstructing a new theatre was promptly published on 3 February 1937. The judging commission of the competition declared the winners to be Aldo Morbelli and Robaldo Morozzo della Rocca.

The announcement of the competition to assign the project of reconstructing a new theatre was promptly published on 3 February 1937. The judging commission of the competition declared the winners to be Aldo Morbelli and Robaldo Morozzo della Rocca.Nevertheless, the project did not meet with great success: dragging on until the war broke out, subsequently resumed with considerable changes, it finally fell through definitively – in part because of the economic recession that imposed a drastic reduction in expenditures – even though the first stone had been laid on 25 September 1963.

5.2 The genius of Mollino

Only two years later, on 25 March 1965, the city administration promoted a new solution, entrusting the work to the engineer Marcello Zavelani Rossi and the architect Carlo Mollino, professor of architectural composition at the Politecnico of Torino and already the author of the Rai Auditorium and the Chamber of Commerce, Industry and Crafts building. The work got underway at the beginning of September 1967.

Only two years later, on 25 March 1965, the city administration promoted a new solution, entrusting the work to the engineer Marcello Zavelani Rossi and the architect Carlo Mollino, professor of architectural composition at the Politecnico of Torino and already the author of the Rai Auditorium and the Chamber of Commerce, Industry and Crafts building. The work got underway at the beginning of September 1967.«After having unanimously planned the general lines of the overall building, Studio Mollino dedicated itself to the sector intended for the public, or rather to the auditorium, the atrium, the foyers and the architecture in general, while Studio Zavelani produced the printouts concerning the scenotechnical sector in its fullest sense, namely the distributive, building, mechanical and functional components of all the relative services».

This is how Carlo Mollino himself described the methods of planning and creating the work, which was designed with absolutely modern criteria, having prevailed, after long and heated debate, the current of thought that believed it necessary to face the problem of reconstruction not on the basis of earlier models but on new architectural and urban orientations.

Mollino had to face numerous problems, especially tied to the fact that the new Teatro not only had to be made part of a pre-existing urban context of considerable historical-architectural importance, but that it was necessary to integrate it with Alfieri’s surviving austere façade.

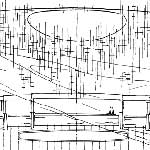

An artist like Mollino could not even think of working in an exclusively conservative sense or in any case be bound to strictly philological aesthetic and architectural canons. His extraordinary personality thus led him to give vent to his imagination by suggesting the old Baroque progenitor through a use of curved lines and sinuosity, an idea as original as it was inspired. Sketch of the Regio hall made by Carlo MollinoThe stylistic constant that more than any other characterizes the external and internal feature of each part of the new Teatro Regio – of which Mollino designed every little detail, from the doorknobs to the lights, from the stairways to the structures in reinforced concrete – is precisely the curved line.

The exterior of the Teatro is characterised by the use of materials that integrate very well with the surrounding edifices. In addition to the brick, the rusticated concrete and the Luserna stone that also covers part of the fly tower, two large windows lighten the external “flanks”, making it possible from the foyers to enjoy the view of Juvarra’s elegant façade of the State Archive (situated in today’s Piazzetta Mollino) and creating a suggestive exchange of vistas between the interior and exterior.

Carlo Mollino could not fully enjoy what can justifiably be considered the total synthesis of his experience: he died just a few months after seeing his artistic-professional testament become operational.

5.3 Architecture and technology

The roofing of the Teatro, in the form of a hyperbolic paraboloid shell, was created by engineer Felice Bertone. By now it is a part of the Turin skyline, like the Mole Antonelliana or the skyscraper in piazza Castello, inaugurated in 1936 and on whose building site the young Mollino did his apprenticeship.

The roofing of the Teatro, in the form of a hyperbolic paraboloid shell, was created by engineer Felice Bertone. By now it is a part of the Turin skyline, like the Mole Antonelliana or the skyscraper in piazza Castello, inaugurated in 1936 and on whose building site the young Mollino did his apprenticeship.The Teatro is arranged over 8 floors, 4 subterranean and 4 aboveground, from a depth of –12,50m to a maximum height of +32m. The offices are in the Alfieri wing towards piazza Castello, while the modern structure accommodates the foyers, the opera hall, the stalls and the stage, as well as all the technical services of the Teatro, including, among other things, two modern rehearsal halls for the chorus and orchestra, a large directing studio, the dance studio, the dressmaking workshop, the cafeteria and another theatre, the “Giacomo Puccini” Piccolo Regio, which has a capacity of 380 seats.

The technical workshops (scenery, woodworking, carpentry and props), once housed in the underground heart of the edifice, are now situated in decentralized locations.

The advanced technology of the structures, constantly modernized to meet increased production needs, place the Teatro Regio in the vanguard internationally: the stage, one of the largest and most mechanized in Europe, makes it possible to accommodate stage sets of considerable complexity, even more than one at the same time.

5.4 The rooms

Seen from above, the plan of the Teatro recalls the hips of a woman, while the stalls look like a partially opened shell. The theatre hall, on an ellipsoidal plan, contains 1398 seats in the stalls and is animated by a tier of 31 boxes that can accommodate up to 194 people. It is illuminated by a large chandelier composed of 1762 very fine aluminum tubes with bulbs and 1900 stems in reflecting Perspex, to create a suggestive “stalactite” effect. The unusual proscenium is obviously inspired by the shape of a television.

Seen from above, the plan of the Teatro recalls the hips of a woman, while the stalls look like a partially opened shell. The theatre hall, on an ellipsoidal plan, contains 1398 seats in the stalls and is animated by a tier of 31 boxes that can accommodate up to 194 people. It is illuminated by a large chandelier composed of 1762 very fine aluminum tubes with bulbs and 1900 stems in reflecting Perspex, to create a suggestive “stalactite” effect. The unusual proscenium is obviously inspired by the shape of a television.The foyers are covered in velvet and vermilion carpeting, adorned with mirrors and finished with quality materials including bronze and marble, and crowned by bare reinforced concrete that shows off the originality and modernity of the supporting structures.

Two symmetrical escalators, placed with great emphasis against the windows of the Tamagno Gallery, have an extraordinary scenographic efficacy. This luxury in the use of the materials and in the grandiosity of the foyers, refined and unequivocal, was justified by Mollino himself with the need to provide Torino with a meeting place of absolute prestige to celebrate with due prominence the great events of city life.

1973-2000

The new Teatro Regio was inaugurated on 10 April 1973 with Giuseppe Verdi's opera I vespri siciliani, directed by Maria Callas and Giuseppe Di Stefano. Since that date productive activity has been progressively increasing, right up to the occasions that have left their mark on the history of the Regio’s recent years: in 1990 the 250th anniversary of its founding, in 1996, live on TV, the centennial of the absolute “première” of Bohème, in 1998 the 25 years of the new theatre. In addition in 1996 the auditorium has been subjected to an important acoustic restoration.

The new Teatro Regio was inaugurated on 10 April 1973 with Giuseppe Verdi's opera I vespri siciliani, directed by Maria Callas and Giuseppe Di Stefano. Since that date productive activity has been progressively increasing, right up to the occasions that have left their mark on the history of the Regio’s recent years: in 1990 the 250th anniversary of its founding, in 1996, live on TV, the centennial of the absolute “première” of Bohème, in 1998 the 25 years of the new theatre. In addition in 1996 the auditorium has been subjected to an important acoustic restoration.

- See more about the period 1973-2000

-

6.1 The inauguration

The new Teatro Regio was inaugurated on 10 April 1973 with Giuseppe Verdi’s opera I vespri siciliani, in the first and only direction by Maria Callas and Giuseppe Di Stefano. The direction of the orchestra was entrusted to Fulvio Vernizzi, the scenes and costumes bore the name of the well-known painter and sculptor Aligi Sassu, while the choreography was by the great Serge Lifar.

The new Teatro Regio was inaugurated on 10 April 1973 with Giuseppe Verdi’s opera I vespri siciliani, in the first and only direction by Maria Callas and Giuseppe Di Stefano. The direction of the orchestra was entrusted to Fulvio Vernizzi, the scenes and costumes bore the name of the well-known painter and sculptor Aligi Sassu, while the choreography was by the great Serge Lifar.6.2 Odissea musicale

After celebrating in 1990 the 250th anniversary of the founding with a large exhibit supplied with an enormous catalogue, the Teatro Regio was enhanced by a new external “curtain”, the bronze gate Odissea musicale (Musical odyssey). It is the work of the celebrated artist sculptor Umberto Mastroianni, who was educated in Turin along with his great friend Carlo Mollino and who had his first important artistic experiences alongside Felice Casorati, Massimo Mila, Ettore Sottsass e Guido Seborga.

After celebrating in 1990 the 250th anniversary of the founding with a large exhibit supplied with an enormous catalogue, the Teatro Regio was enhanced by a new external “curtain”, the bronze gate Odissea musicale (Musical odyssey). It is the work of the celebrated artist sculptor Umberto Mastroianni, who was educated in Turin along with his great friend Carlo Mollino and who had his first important artistic experiences alongside Felice Casorati, Massimo Mila, Ettore Sottsass e Guido Seborga.6.3 Centenary of Bohème

1 February 1996 was the centenary of Giacomo Puccini’s Bohème, the absolute première performance of which the Regio had the honour of hosting with the direction of Arturo Toscanini. For the occasion Mirella Freni and Luciano Pavarotti met on the Torinese sets, under the baton of Daniel Oren. The show, directed by Giuseppe Patroni Griffi, was broadcast live on Rai Due television, in prime time, with an audience of over three million viewers.

1 February 1996 was the centenary of Giacomo Puccini’s Bohème, the absolute première performance of which the Regio had the honour of hosting with the direction of Arturo Toscanini. For the occasion Mirella Freni and Luciano Pavarotti met on the Torinese sets, under the baton of Daniel Oren. The show, directed by Giuseppe Patroni Griffi, was broadcast live on Rai Due television, in prime time, with an audience of over three million viewers.The Piccolo Regio theatre was renamed Piccolo Regio Giacomo Puccini on the same occasion in honour of the composer who had seen several of his operas commence in Torino.

6.4 Acoustic restoration and anniversaries of the new Regio

In the summer of 1996, the auditorium of the Regio underwent an important restoration planned by the German firm Müller BBM , for the acoustic part, and by the Gabetti & Isola firm for the architectural restyling.

In the summer of 1996, the auditorium of the Regio underwent an important restoration planned by the German firm Müller BBM , for the acoustic part, and by the Gabetti & Isola firm for the architectural restyling.The intervention, reversible in each part, involved wood-panelling the auditorium, slightly modifying the external walls and stage and installing a new proscenium over Mollino’s structure, which caused an increase in the acoustic connection between orchestra pit and stage. The

achieved result was particularly appreciated by Claudio Abbado who, in May 1997, directed the Berliner Philharmoniker in Verdi’s Otello with stage direction by Ermanno Olmi. That opera was also broadcast live by Rai Due to very favourable reviews.

achieved result was particularly appreciated by Claudio Abbado who, in May 1997, directed the Berliner Philharmoniker in Verdi’s Otello with stage direction by Ermanno Olmi. That opera was also broadcast live by Rai Due to very favourable reviews.The 25th anniversary of the birth of the new Teatro Regio was celebrated in 1998 with "D’Opera", an exhibition of scenery, props, machinery and costumes mounted in the suggestive spaces of the Cavallerizza and attended by over 70,000 visitors. The Baroque views of the old Torinese military quarter located just behind piazza Castello paid tribute to the extremely suggestive setting.

From 2000 till today

The new Century has meant to catch the opportunity and the challenges connected to the juridical transformation of the operatic organisation into private law foundations. In 2006 the extraordinary experionce of the XX Winter Olympic Games and of Culture's Olympic Games, which have put the Teatro Regio in a central role with a huge number of shows under the watchful eye of the international public, have acted as a springboard for the relaunch of the Reagio all over the world. This also thanks to the artistic partnership with Gianandrea Noseda, appointed Musical Director from 2007 to 2018. Those were years during which the Regio has been invited many times on tour: in Japan and China, in Saint Petersburg, in many citues and European capitals (among the others it has been Edimburgh and Savonlinna Festivals' guest), in United States and Canada, in Argentina and Oman. At the same time the market presence of our video-record production has been very much increasing and this goes simultaneously with our significant participation in the european project OperaVision, from its birth.

If you are conducting a research or you have specific requests you can contact the Historical Archive of the Teatro Regio.